Knowledge Sharing is Critical to Delivery and Growth

02 Oct 2015Software development is hard, especially at scale with code in production. You are constantly trying to switch out the engines, support beams, and window panes of an airplane while it’s in-flight. We create processes for how we track issues, organize and submit code, and prevent regressions as a means of dealing with complexity. These are the rails that our organizations operate on so we don’t crash into the ground. A cornerstone of these processes is how history (why we made certain decisions) and direction (where we are going and why) are recorded, translated (between development, product, etc), and disseminated. Which are essential ingredients for teams and individuals to build incredible products autonomously with as little friction as possible.

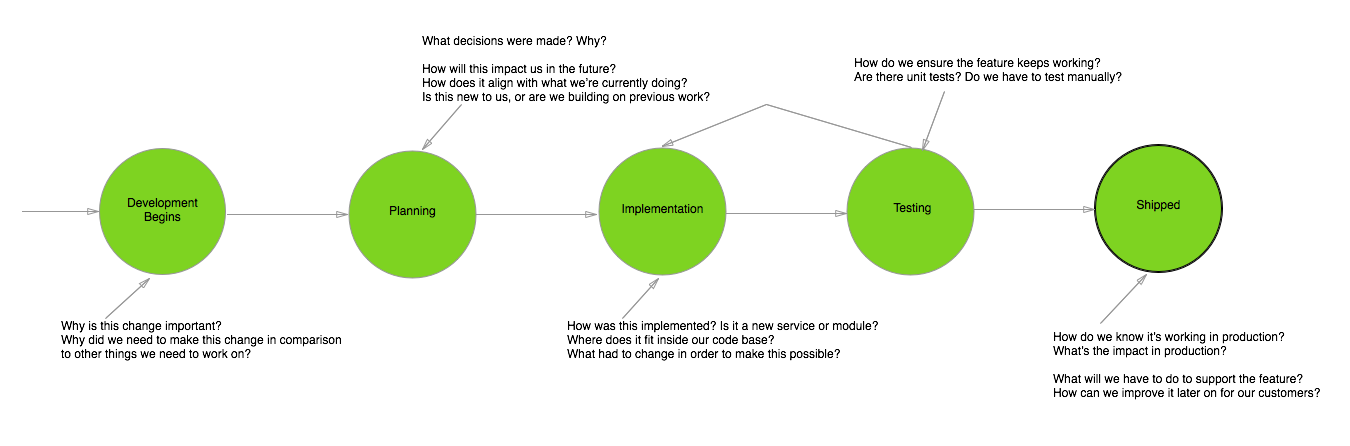

For a developer to make the most effective change to a code base they must understand how the system operates, what decisions led to that state, and why. It also means understanding how different components of the system are designed, tested, deployed, and behave in production. This knowledge is often times the by-product of the development process (illustrated below) and tends to be locked up into a few individual’s heads (the person who implemented the feature and perhaps the code reviewer).

At first glance, these questions seem trivial but this information will continually impact the cost of development (tech debt, supporting multiple systems or frameworks, etc). One example of this cost is ensuring that the system continues to behave as intended after a change has been made. A popular way we’ve dealt with this complexity is by writing automated tests that run after every change to ensure we haven’t regressed on any important behavior. What we’re really doing is recording how the system should behave so others, including computers, can leverage this knowledge.

Understanding our past allows us to make changes to the system and deliver them into production successfully. On top of this it helps shape our vision of how the system will work in the future. Which brings us to the second important component of any knowledge strategy: communicating the intended direction and creating alignment.

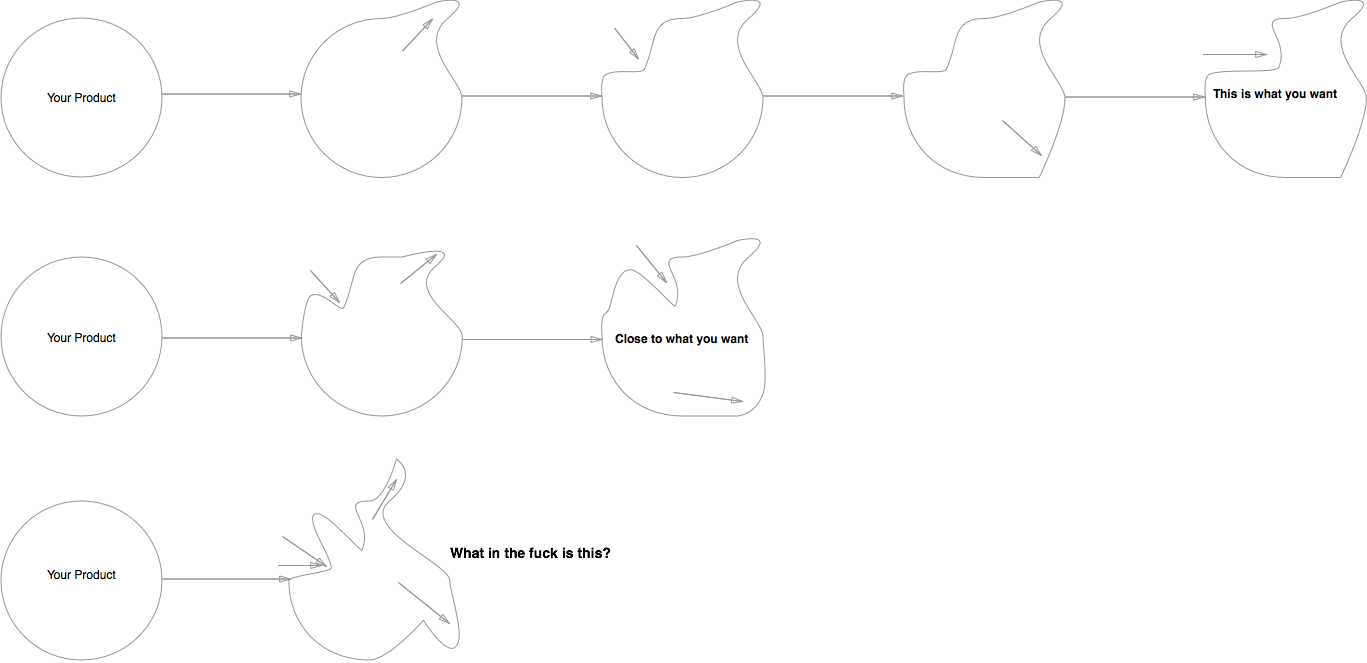

How and when should we be logging events? Are there certain patterns we should be emphasizing or avoiding? How and when should we be committing transactions? Should we be adding more responsibility to this module? These are the types of questions that if they go unanswered will quickly lead to a spaghetti code bases. The impact of lacking alignment is multiplied by the number of people working on the same code base (which I’ve illustrated below). This is a problem that becomes increasingly difficult to manage as the number of developers contributing to a code base increases.

While you may get to a place faster (because you can do more), it’s not necessarily what you want or need from the system. This is because developers tend to work autonomously (good) which enables you to parallelize the amount of work being done (also good). The problem is that they’re making changes with incomplete knowledge about where the system needs to go (bad). This tends to end with developers either stopping to ask questions (good and bad, they are no longer working in parallel and autonomously) or they fill in the gap with their own ideas (bad -- if your goal is architectural correctness and avoiding spaghetti code).

There are many ways to handle this problem such as having an “architect” role (which has mixed results) or some sort of upfront review process for changes that impact the system’s design (depending on the format this can work really well or it can be incredibly toxic). However, nothing is more important than frequent updates from leadership on the direction and priority of product, technology and engineering process. If these things are clear then developers are equipped with the best information about the road ahead and can make the most effective and efficient decisions about the changes they are implementing.

When and how you think about solving these problems is completely dependant on the size of your system and development team. If you are small, it’s easy to stay in sync and you make decisions quickly. As you grow, ensuring everyone has the right historical context and is aligned about where you’re going becomes incredibly difficult. Which can lead to amassed technical debt, a spaghetti code base, and hardened knowledge silos (only X knows how Y works). Ensuring you are building the right processes to record and distribute this knowledge will help you to navigate these challenges and allow you to keep delivering incredible products.